Bard Sequence Seminar Podcast

Join the Bard Sequence as we explore great works of literature, philosophy, and history from unique perspectives.

https://bhsec.bard.edu/sequence/

Contact Us: sequence@bhsec.bard.edu

Keywords: Literature, great books, books, reading, culture, fiction, book lovers, good reads, classics, novels, arts, education

Bard Sequence Seminar Podcast

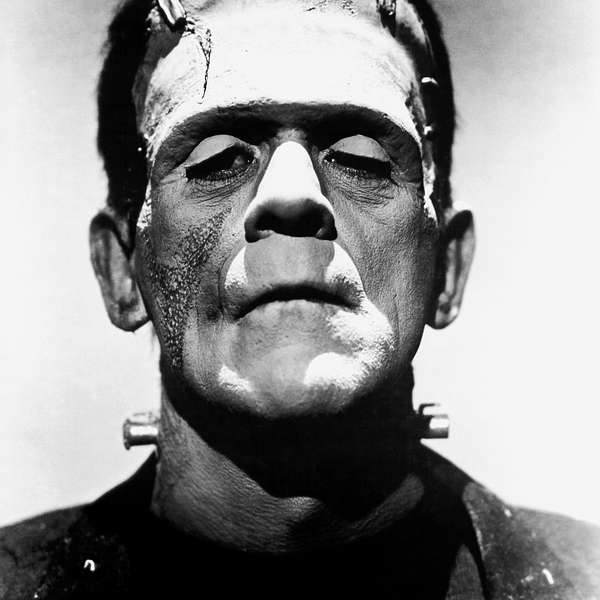

Frankenstein x Horror

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

In which our intrepid panelists make connections between horror films and Mary Shelly's seminal horror text.

Featuring Rosa Schneider, Katherine Bergevin, and Matt Park.

Content Warning: Between 1:12 and 1:14 a stage adaptation of Frankenstein which features sexual assault is discussed. There are no graphic descriptions, but anyone who does not want to engage with this content will want to skip.

Spoiler Warning: Spoilers for the film M3gan as well as some much older movies.

As always, reach out to sequence@bhsec.bard.edu with comments!

Matt Park

Let me go, he cried. Monster, ugly wretch. You wish to eat me and tear me to pieces. You are an ogre. Let me go or I will tell my papa.

Welcome to Bard Sequence Seminar podcast. Today it's a connections episode, Frankenstein and Horror. I'm Matt Park, director of the Bard Sequence, and today I'll be your friendly moderator and panelist. I'm joined once again by Rosa Schneider and Catherine Bergevin. Catherine, Rosa, please say hi and introduce yourselves one more time.

Rosa

Hey everyone, my name is Dr. Rosa Schneider. I was a Bard Sequence Seminar teacher for three years at Orange High School. And I am now at a New York public school in the Upper East Side. I'm really excited to be here. Frankenstein is one of my favorite books to teach, books to read, and connections to make. So I'm excited to dig in.

Katherine Bergevin

My name is Catherine Bergevin. I'm a PhD candidate at Columbia University's Department of English. And I'm also the Director of Operations for the Keats-Shelley Association of America. And that includes Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein. So I am both personally very interested in Frankenstein and the horror genre, and also have a professional interest in promoting young people's interest in the text. I'm really excited to have this conversation.

Matt Park

Thanks, Catherine and Rosa. This episode of the podcast, it really started from what you said in the original Bard Sequence Frankenstein podcast, which none of the other panelists were really ready to kind of take up, which is the horror connection. And I love horror movies, but I was only the moderator on that podcast and thus was unable to jump in and just like hijack the conversation and be like, yes, let's talk about horror the whole time.

So we didn't. So I figured this would be a great way to do that, would be to have a connections episode where we connect the classical text, Frankenstein, to something more contemporary, horror movies. And my premise is that a lot of people love being scared. And by people, I mean some people. I know plenty of people who can't or won't watch horror movies or read scary stories. Personally, I think they're missing out, but that's just me.

When you look at it, human societies have told scary stories about terrifying creatures, monsters, ogres, witches, goblins and orcs and dragons and man -eating whatever and so on for about as long as we've been telling stories, as long as we have evidence of human storytelling, we've had these kinds of stories. People sitting around a fire and just scaring each other.

And Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, written during that long, dark and dreary year without a summer of 1816, it certainly does fit into this tradition. And I think the quote at the top of this episode shows that pretty well. William Frankenstein accuses the creature of wanting to eat him, calls him an ogre, and draws on some of these older folk horror stories that I think certainly are informing some of what Shelley is doing in Frankenstein.

And I think the reason that these stories are so old is that they have been told by society and part of their goal was to reproduce societies, these societies themselves, by providing a kind of warning to listeners. If you act out, if you go where you shouldn't, if you defy the laws or the gods, something terrible will surely happen to you or to us all. And that is certainly one of the functions of horror, historically speaking.

We can see that in some of the horror tropes which have made it into Hollywood movies. Characters who are promiscuous are killed off first. Overly curious people pay the price for poking their noses about. Characters who defy the laws of gods and men bring about terrible calamity. People who dig up the past find terrible things that should have remained buried. And those who seek inhuman power end up suffering when they get it. Fear -based discourse can be pretty powerful in shaping human behavior.

But I don't think that an answer that only focuses on how horror reinforced structures and orders in society, it doesn't quite capture the ambiguous experience that a horror film or reading Frankenstein has on the audience. If horror movies primarily attracted people because they provided such stern warnings about antisocial behavior, we wouldn't find that teenagers are the main audience for the so -called dead teenager movies and slasher films. And yet they certainly are the main audience. Teenagers show up to be scared by images of dead teenagers.

And I think one of the things that horror has always done is to make people feel alive or to remind them that they're alive and actually encourage them to live more fully and sometimes even to take risks.

At the physiological level, we could look at what happens to people when they watch horror movies. We could look at increases in things like adrenaline, endorphins, dopamine, all biochemicals that kind of make people feel a little bit high. It gives them a bit of a rush. It certainly makes them feel alive, gets the blood pumping, you know, the capillaries kick into action and all these kinds of things. And I think for some people that's enjoyable.

Not everyone enjoys that feeling, right? But for those who do, I do think it's a bit of a rush. I think for others, horror films genuinely help them to work through some things, things that might be going on in their lives or in their heads. Seeing a dramatized version of their inner turmoil might actually be therapeutic. It helps people work through some dark thoughts or some dark things that they're going through in their lives.

I tend to fit into the latter category. That's why I enjoy horror movies. I don't like the jump scares. I don't like the adrenaline and endorphin rush of being frightened. But if a horror movie allows me to examine the darkness, the darkness within, the darkness without, I can tolerate the scares that come along with something jumping out of the darkness and quickly frightening me. I don't enjoy that, but I will tolerate it so long as the movie is making me think. And so I think at the heart of horror and especially modern horror films, it's a bit paradoxical in which the film warns the audience about the consequences of pushing boundaries and yet, what the film doesn't acknowledge is that it, for some folks at least, it has the opposite effect.

And so one of the questions that I thought about when thinking about the way that horror impacts people, how many readers of Frankenstein, even after reading this novel about brutal suffering that's unleashed, when Victor Frankenstein defies the laws of gods and men and creates life, how many people would ultimately make the same decision if they were in his shoes? If I had the power right now to walk down into my basement and flip a switch and create life, would I do it? I don't know if I would or wouldn't, but I would certainly think about it. So for me, that's kind of what horror is and why horror is interesting to me, why I like horror films and the kinds of films I like.

What do you think? Catherine, Rosa, where do you weigh in in terms of what is horror? Why do you enjoy it? Why do other people enjoy it? What do we make of it?

Katherine Bergevin

I have an immediate response to your comments, Matt, and then I have a response that's more personal to me that I had been thinking about before we got started recording. And you asked the question, you know, how many of us would repeat Victor Frankenstein's actions? Or I think what you really meant is how many of us would repeat his mistakes, even knowing that they're mistakes? Maybe that's not exactly what you meant, but I felt like that was a bit of the subtext.

And I think part of horror movies for me, especially when I was watching them with my friends as a kid, was the sort of deconstruction you do as you're watching them and afterwards of like, well, what would we have done or what would I have done in that scenario? And it's almost like a way of like soothing yourself after being scared. And you might say like, oh, I would have run away from, you know, the huge monster in this way that they didn't think of or, you know, this is how I would prepare for, you know, the zombie apocalypse outbreak. I feel like I've sat down with my friends and actually talked this through in a really intense way so that was part of it. So I think there is also that process of, like, self-protection and feeling like you're smarter than the characters. Like we would never split up, you know, like they do on Scooby -Doo, because like that's, you know, you always end up dying one by one in that scenario. So that's what I was thinking as you were speaking just now, Matt.

But the thought I've been having earlier when you had sent us the questions and I was reviewing them before we started recording is that I think for me, a big part of why I like stories in general is just I love the feeling of escapism. I mean, I'm sure that's true for most people, but because horror movies are so good at just grabbing you and putting you in the moment because they're plugging into all these sort of physical responses that a person has to frightening images and frightening scenarios, it's like the fastest route to escapism. And ironically, it makes you feel really present in the make-believe world of the film in a way that I find can be harder to achieve with other genres. So even if it's kind of a crummy movie that's really cheesy, you know, seeing violence or just seeing a terrifying monster, I feel like I'm kind of like there in a way that allows me to just step out of my own, like really quickly. But then the flip side of that is I love horror movies but I get - I used to get really bad fear of the dark until I was actually, you know, an older teenager. So it would come back to haunt me when I was trying to sleep later. But it always seemed worth it. I would torture myself in this way.

Rosa

It would come back to haunt you. It's horror.

Katherine Bergevin

Yes, literally.

Rosa

That's why I'm here for my jokes. You know, Catherine, I have also thought very extensively about what my role would be in a zombie apocalypse. And I realized that I would just die. Like I have no survival skills. I can't drive. I can't ride a bike. You know, I can roller blade, but I don't know how fast that's...

Katherine Bergevin

Do you think the highest risk way of dealing with zombies is rollerblading?

Rosa

Yeah, exactly. So I think I would just check out. I was like, nope, then this is for me.

That is, yes. I agree with both of you guys. I think horror movies and going to that, going to horror movies is definitely a sort of catharsis. That you go and you kind of like watch all of this horrible things happen to these people and you're like, thank God it's not me. Or you work through those emotions and you kind of purge them. I hate horror movies, honestly. Like I truly, truly hate them. And all of my students love them so much. And whenever we had a free day, they were like, let's watch The Conjuring. And I was like, do we have to? Is this, do I have a choice? But I would always give in because they love it so much. But yes, I'm not a horror fan. The only way I like to watch horror is to watch it when it's mixed with something. So think like humor. Before we knew all the problems with Joss Whedon, I really loved Cabin in the Woods, right? You know, it was horror, but it was also humor or social commentary.

Get Out is something that I think I talked about on the last podcast. All of basically Blumhouse's horror, just like that's the horror I can see if it's in service of something else.

Matt Park

So I don't know the problems with Joss Whedon. I don't know if you should tell me or not. I don't follow media that much or famous people. So what are the problems with Joss Whedon?

Rosa

So it turned out that his, you know, yay, feminism was actually hiding a pretty deep misogyny. He forcibly, you know, he assaulted some of his cast members, the cast. He, you know, really insulted a lot of other people. You know, look up Charisma Carpenter, her... her whole thing with Buffy and Angel was just horrible. He got Me Too'd essentially a little while ago and it was sort of that whole generation.

Also horror, right? You know, the horror of sort of like knowing, learning, learning that something that was like Buffy, I don't know about you guys, but Buffy is so deeply ingrained in like my sense of being, but knowing that like it's made by someone who's terrible is a hard thing to take.

Katherine Bergevin

Well, I think, um, I actually, I never really watched that that much Buffy. So I don't know how applicable this would be, but I think with Me Too, like part of it is as it applies to like film, you realize sometimes that like scenes of violence you're seeing depicted on screen might, you might actually be watching on a certain level, a recording of someone experiencing actual violence, like whether they've been sort of coerced or pressured into maybe like appearing nude in film or they're being subject to pressures like off screen that make it a hostile work environment. And so I think it does introduce that tension. That's probably ancillary what we're talking about here.

Rosa

Well, I mean, like, Kill Bill, for example, that the scenes with like Uma Thurman at the very beginning were basically real, right? Like, so like when she's being like beaten and when she's like all of these things, like there were like actual physical violence that was happening to her on that set.

And so it is really sort of interesting to go back to be like, you know, whereas we like horror movies for some, you know, because the violence is, you know, fictionalized, right? We know that like, these people aren't, you know, in the Saw franchise, they aren't having their like, you know, arms really cut off, right? Or, you know, whatever is happening to them. But, and then, then when we learn those things and we go back to those movies, you're like, oh no, this violence is like, this isn't cathartic violence, it's just straight up violence.

Katherine Bergevin

It almost makes me think of how when you go back and watch really old movies and you realize, oh, they actually shot all these horses in the course of making this classic war film or, I mean, not to equate violence against people, violence against animals, but it's also very problematic and upsetting, obviously. Or even I was watching a movie from the 70s, where a man, I think it was a Aguire Wrath of God, it was a Werner Herzog movie where a man picks up a monkey and just kind of chucks it. And you're like, oh my God. You know, it kind of takes, it actually takes you out of the film now because you realize that animal abuse was actually happening on set. So it's, for us now it breaks the sense of escapism.

Matt Park

So I don't know if you've noticed, but we are in the middle of the Frankenstein-aissance or the Mary Shelley-sance. We have a number of films coming out just in the past year. We have Lisa Frankenstein. We have a Guillermo del Toro adaptation of Frankenstein. Just in the past five years, we've had a ton of adaptations, which is great timing for our next category, which is Mary Shelley, Influencer.

We're gonna take a look at the influence of Mary Shelley's book, Frankenstein, on horror and other horror -adjacent movies. Before we do that, why are we in the middle of the Frankenstein-aissance? What is it, you think, that is causing so many remakes, movies, TV shows, to be made either about or influenced by Frankenstein? Why are we at this moment?

Rosa

I mean, I think it's sort of a, it's a story that can never really get old, right? We're, I think, always fascinated by like, by death. We're always fascinated by, you know, can we conquer death? Can we, you know, we have so many other scientific advancements. Why can't we do this? I think that's really important. I also think just like the pushing of technology, right? Like there's so, little difference now between like technology and sort of the human body or what we can do. The Google glasses are back, right? Or not the Google glasses, the Apple Vision Pro. They're now Ray -Bans I saw on Instagram where you can like click and take pictures, right? The line between technology and the human body has like totally vanished basically. And we're always sort of thinking about that. So I think one of the reasons why Shelley and these Frankenstein-esque adaptations, right? I also wanna add Poor Things.

Matt Park

Is it Elon Musk and Zuckerberg? Is it AI and the tech bros who think that they're gonna live forever? Right, I mean, that's part of what I'm wondering. If it's not a generalized fear and response to AI and the idea that AI is going to replace us and the idea that some tech bro in Silicon Valley is going to figure out how to actually become immortal.

There are news stories that have been popping up in my feed lately, and maybe that's because I click on articles about Frankenstein and immortality and the algorithm decides I need to know about the latest tech bro who claims he's gonna live to 250 years or something. So I guess the algorithm is kind of feeding me what I'm interested in. But it's certainly being talked about. There are people who are talking about extending their lives, living forever. And I wonder if that's not part of what's driving at least some of the Frankenstein-aissance.

Katherine Bergevin

I'll just jump in. I have, maybe it's a little bit of a sideways or answer to what you just suggested, Matt, but I kind of wonder if a bit of the Frankenstein or Frankenstein-aissance, I like that phrase, which is also great because Frankenstein is about like reviving things from the dead and then that's what Renaissance means. But um, could it be a bit of a corrective or could we embrace it even if this isn't like the true root cause as a corrective to sort of the very selective or even arguably false story of science fiction that you hear a lot of from the sort of tech bro Silicon Valley community. The idea that, you know, sci -fi started with someone like Asimov or Philip K. Dick, like this fixation on a very... male -centric view of science fiction where you go from iRobot right into Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash, which is another really influential book for this crowd, which is about a virtual reality. Incidentally, I personally think it's a very misogynistic book as well, or at least sidelines women's subjectivity in a big way. And I think having all this Frankenstein content available is a way of pointing out sci -fi is much older than this. It has a much more complex history. And I'm not deriding these authors like Philip K. Dick or any of those classic guys like they're...

Rosa

I will.

Katherine Bergevin

Okay, I mean, if you like them, I don't think they're like to blame for, you know, the current AI situation or anything like that. But I think it's also not a coincidence that we have this resurgence of interest in a science fiction novel that was written by a woman that does create more opportunities for directly looking at like masculinity as a constructed entity in our culture.

Rosa

I totally agree. And I also think that one of the things that make it so interesting as a sort of birth of science fiction, unlike a lot of Asimov, Dick, even Jules Verne, a lot of the other sort, you know, fathers of sci -fi, one of the things that's so fascinating about Shelley is that, and Frankenstein, is that it's in our world, right? It's so in our world, and it's the birth of Frankenstein and the, excuse me, the birth of the monster, I apologize to all my, also all my students at Orange, because I kept drumming that in. The birth of the monster is what is science fiction about it. And not the sort of, the world of it, not anything else. It's just that kind of fact, the bringing to life. And so that because it is so recognizable and because you can put it in so many different things.

Just thinking about the recent adaptations we've seen. So like Poor Things, a baby's brain is put into a woman. Or Lisa Frankenstein is about like a serial killer. Or I am excited for the Guillermo del Toro, I haven't seen that one. Or as I will probably later argue, like M3gan is an adaptation of Frankenstein and that's just like one little thing. So that it's a very copy and pasteable argument, which is I think kind of really interesting for what Catherine said.

I also want to touch on the AI thing that Matt was talking about. And like AI, where it has all of this knowledge at its disposal, basically anything that has been uploaded to the internet and it misreads it. In the same way that like the creature misreads all the things that he knows. He sees Satan in Paradise Lost and says like, yeah, that's my guy. Like that's the, he's the hero of it, right? I'm him, right?

Katherine Bergevin

Well, structurally, Satan is the hero of Paradise Lost. Oh, okay, we're gonna have like a...

Rosa

Well. Okay, the good guy. You're right, he is the hero, he is the main character, he's the dude, but he's the good guy. And so like that kind of thinking about like some of my students' AI work, I'm like, yeah, that feels so relevant.

Katherine Bergevin

Well, I thought what's interesting is I thought you were going to say that Victor is, uh, I thought you were going to bring him up rather than the creature. Cause he is in a way kind of like this UR tech bro or our idea of what that person is. He has all the world's knowledge at his disposal. Um, he goes back and reads all these classics and then his professors are like, you know, this is totally obsolete and irrelevant, but he kind of, you know, tears down that path anyway. And he does discover some knowledge that's been lost through history, but he also doesn't absorb any of the sort of like ethical teachings of, you know, the more recent moment or other work that's been done. He doesn't listen to the voices of the people around him who are kind of like, are you okay? You know, he doesn't really absorb the values that he's getting from, you know, his parents or from Elizabeth. And he makes this really reckless mistake that out of hubris that ends up, you know, destroying the people around him. And his I don't think his narcissism is ever really punctured by the end of the text either.

Matt Park

He's a disruptor. He's there to disrupt, you know? And you cannot burst that bubble of confidence. Once they've decided to disrupt the system, the system must be disrupted, and that's it. Plus, he's got mommy issues. That's another thing.

Rosa

To say the least. You know what? I'm gonna change my answer to that. I agree.

Matt Park

All right, so here's the list I came up with. These are horror and horror adjacent films that I at least see a direct influence of Frankenstein on. If I miss any, please add them. And then I'll have one at the end that maybe we can talk about. So I came up with May, Poor Things, Splice, Edward Scissorhands, Reanimator, M3gan, The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster, Eraserhead, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Jurassic Park, The Island of Dr. Moreau, The Lawnmower Man, and then we have all the AI films, so 2001: A Space Odyssey, Alien, Alien Resurrection, Alien Prometheus, Alien Covenant, AI, Ex Machina, Avengers: Age of Ultron, iRobot, Terminator, and all the Terminator sequels.

And then some films I'm going to be talking about a little bit later, which are Godzilla, Shin Godzilla, and Godzilla Minus One, as well as any of the ones with Mechagodzilla for technology reasons. Other things that should be on that list or films that you'd like to single out.

Katherine Bergevin

Well I just watched the Prometheus film that came out I think in 2012 now, which is shockingly long ago in preparation for this podcast. And I also want to add The Nightmare Before Christmas.

Rosa

And I will definitely want to talk about M3gan at some point as well as Get Out.

Katherine Bergevin

Oh, and The Stepford Wives, if we're going to talk about get out.

Rosa

Oh, definitely.

Matt Park

Excellent. I liked Alien Prometheus. I thought it was quite good.

Katherine Bergevin

I did too. I had a very... I went to see it with one of my best friends and we were riveted in the theater. And then as soon as the credits rolled, all these sort of like men sitting around us stood up and were like, that was the worst movie I've ever seen. And we were flummoxed. So I, it's nice to meet like a guy who understands, you know, science fiction. Sorry, man.

Matt Park

So that's the next place I'm going is we're talking a lot about men today and that probably is gonna continue as we go. But the other film, so I was going down a list of just horror movies as I was preparing for this and coming up with this list of influences. And one of the ones that struck me was The Invisible Man. Because The Invisible Man, it's kind of like a mirror on Frankenstein.

Science creates something that it shouldn't have. A man is turned invisible. And yet he has the opposite problem as Frankenstein's creature. Frankenstein's creature's problem is that it's enormous and anyone looking at it sees its, quote, yellow skin and deformed features. And it looks like an ogre to people. People see it and they think, ogre, this thing's gonna kill me, this thing's gonna eat me. They scream, they call the authorities, they run away and they ostracize him. The invisible man has the other problem, which is literally no one can see him. And yet the invisible man also goes on a killing spree. So I guess what I was wondering is, is the man part the problem? Is it, you know,

Or let me put it this way, if Victor Frankenstein had created a female creature, would the story be different? First of all, would people have treated the female creature differently? And then, or even if the female creature was treated very similarly, very poorly, would the female creature have done what the male creature did, which is go off on the murderous spree? Would the story change essentially if Victor Frankenstein's creation is not male but female?

Rosa

I think it would. I mean, a lot of the reactions that people have, as you mentioned, to the monster, to the creature, was just his sheer kind of size. And maybe that would be different.

Um, there's also the, the fact in, you know, and Katherine can speak more to this, right. In, you 19th century Europe, gender was much different, right. And so a woman walking alone, even sort of a deformed, probably deformed woman would have been treated a lot differently. Maybe given access to different things or not given access.

Yeah, that is an interesting question because have you guys seen the, I think it's the 2001 Frankenstein with Carrie Anne Moss as Victor?

Katherine Bergevin

I don't think so, no. I would have remembered that.

Rosa

Yeah, Carrie Anne Moss as Victor and a hot creature. Like he's basically, he's like, just, they just brought a guy back to life. Um, and yeah.

Katherine Bergevin

That was what Victor wanted to do. He says he had selected the... he wanted him to be beautiful and he did not succeed in, you know, that quest. But probably his idea of a perfect, quote unquote, or beautiful woman would have been different from his idea of, you know, the ultimate man. It probably would have been physically less strong and smaller and all these things. I think you're right, Rosa.

One thing I did think of as you were speaking, Matt, was Victor does, you know, in the course of our text, briefly create a female creature and obviously that's not his primary creation, so this isn't to contradict what you said, but he ends up destroying her and I find it really fascinating that he destroys her because he's so afraid of the reproductive potential that she presents. Like he sees that as being the thing that makes her existence particularly monstrous and frightening. And I think if he created say like or don't endeavor to create like this perfect female reanimated creature.

He assumes that she and the male monster would be able to reproduce in the text. So probably her having like, reproductive capacity would have been integral to his idea of creating like a perfect woman. And I think this might also tie into why Frankenstein feels so maybe relevant or of interest to people right now is like we are in a moment where human reproduction is becoming so much the focus of political attention, like in the States, but also in a lot of countries, like around the world. And even beyond the question of like gender equality and autonomy, there is this, I think discomfort that people seem to have with just like in general, the human capacity to reproduce itself. And it's like, whose responsibility should that be? Does the right to do that really lie with the individual? Like, is it something that society has to like authorize? Or does society have the right to prohibit in some cases? And so Victor, he is producing a monster in this really, or a creature in this monstrous way, I should say, but he doesn't want that creature to be able to reproduce. He doesn't want it to have a female companion. So I think the female version of this creature would be defined by probably like her sexual appeal to certain men. Like that's what Poor Things I think explores. Even Nightmare Before Christmas, like a children's like sanitized version of this, I think like the character of Sally, her role as like wife slash daughter is very unstable. Anyway, so I think I got kind of maybe off track there.

Matt Park

No, that was great. How quickly would there be laws specific to the womb of the creature to make sure that their regulation, that their reproduction rather was properly regulated?

Rosa

God!

Katherine Bergevin

Six months. Yeah, immediate.

Matt

There would be an executive session of

Rosa

The Vienna Council.

Matt

whatever the appropriate governing body would be to quickly draft some laws about the reproduction of the creature.

All right, next category, I'm calling this one, It Came From the Deep. And we're gonna take a deep dive into some films that we believe are connected to Frankenstein and talk about the connections we see and the influence of Frankenstein on those films.

Rosa

Honestly, I have like a folder now. I feel like my life has just become Frankenstein connections and I haven't taught Frankenstein a little while, but I feel like if I, if I can, I will just like be going on and on and on and on. So it feels like my life is Frankenstein.

in a little bit. So maybe that's the horror film. I can't get away from it. But yes, I think one of the things that I find really interesting is sort of how the Frankenstein narrative kind of creeps into things. And my sort of favorite Blumhouse horror story is M3gan, which is a movie about a robot, who is made sort of a last ditch effort by its creator, but is made to protect or to be a companion for a kid. Initially it was made to be the last toy you'll ever buy. And also that I think ties into a lot of what Victor says himself in the Frankenstein text, that he wants to create a new race of people, right? A new sort of people who would inherit the earth.

So anyway, for those folks who don't know, right? M3gan is about this very lifelike robot who is being tested by the creator, by the creator, and she pairs it with her niece whose parents have just died in this horrific car crash. And so she pairs it and then they kind of see how the robot sort of develops and how they get to know each other and they get to be really fast friends. And suddenly the robot is providing all of the emotional support that the aunt should do, but isn't. And the robot ends up taking her job, protective job too seriously, right? That she, the minute there's a threat, like for example, the neighbor's dog bites or attacks the little girl. So M3gan goes and kills the neighbor's dog, right? And then M3gan goes and kills the neighbor. And then M3gan goes and kills, spoiler by the way, I'm sorry, I should have said that before, goes and kills the little kid, the little boy who kind of torments her, right? And then it kind of gets more and more and more and more and more until M3gan sort of takes over and like becomes like totally evil and tries to kill its creator.

So one of the things that I found, you know, the film really interesting is that I think there's like a moment in the final scene where M3gan is facing off against her creator who is played by Marnie Williams, not Marnie Williams, oh my God, that is not her name, what is her name? Brian Williams' daughter, who was also in Get Out.

Katherine Bergevin

Alison Williams.

Rosa

Allison, thank you. Marnie is her Girl's character, speaking of creeping things. And she's facing off against Allison Williams. And she's like, well, why did you create me then? I'm doing what you wanted me to do. And they fight. And then of course, the robot ultimate look loses.

But yeah, so that's one of the things I found kind of that was such an interesting connection where it's just like, this is a creation is spurned by its creator for doing exactly what it was supposed to do, right? There's too much of a question about what is life. M3gan is way too lifelike. It's gone like beyond the Valley of the Uncanny, right? It's, you can't, people couldn't tell that she wasn't a human. It's different than the creature because she's perfect and she's not like ugly, but it's still this sense of like, you created this technology and now what are you supposed to do?

Matt Park

Thanks Rosa. Catherine, what is your film?

Katherine Bergevin

So the film that I wanted to speak about is The Nightmare Before Christmas. It's kind of a different vibe than M3gan probably. But the character I was really interested in was Sally, who is a rag doll, sort of scarecrow who's been sewn together and is stuffed with leaves. And she's been created by sort of a mad scientist type of figure, who when I was a child was the scariest possible entity to me. Like I was convinced he lived under my bed and was going to kill me if I turned the lights off before going to bed. So to me this was a horror movie as a small child, though I don't find him as scary anymore.

But what I find really interesting about Sally is that she's clearly been created as some kind of ideal woman. It's not really clear what her relationship is to this guy who created her, whether he wanted her as maybe like a daughter or a wife or sort of a nebulous combination, just sort of generic female companion. Her role is like to prepare food for him. And she's been made with these really tiny feet that she has trouble walking on. And he's always telling her at the beginning of the movie, like you, we need to wait longer before you're ready to go out into the world and experience new things. And we kind of see as the film progresses, this character is able to walk more confidently, like she's not stumbling around as much. These are things I didn't really notice as much when I was a kid, I think. But what I find really fascinating about Sally is the way she's animated. I mean, what I think the stop motion really draws attention to also the role of the artist in creating the film in a way that you kind of lose with like the 3D animation that kind of dominates everything now.

But she's constantly kind of taking herself apart and reassembling herself in order to kind of like trick people around her or cleverly navigate situations. And there's a scene at the beginning where we see the, I can't remember if he's called a professor or a doctor, even though I just watched the movie last night, he grabs onto her arm because he wants to control her and stop her from running away from him. And she just cuts the thread and runs away without her arm. And so, there's a way that she's definitely a reference to Frankenstein's creature. We see him, you know, he reanimates the skeletal reindeer that are attached to Jack Skellington's sled later on, and he has a assistant named Igor.

So clearly he's like a Dr. Frankenstein kind of figure, but she's like a version of the creature who is able to kind of like take advantage of and take control over this strange like anatomy, that she has, which is an assemblage of disparate parts and kind of use them to her advantage. And I think her and her being female is obviously really important. Like she's the love interest for Jack. But also there's a scene where she takes her leg off and she uses it to distract like the villain, Oogie Boogie, which is very weird watching this again as an adult. And he's, totally, you know grabs at the side of this like sexy leg, but then he realizes it's disembodied and her disembodied hands are being used to, you know, rescue Santa Claus. Meanwhile, in the background. So she's not an assemblage of parts that were from a graveyard, but she is kind of an assemblage of parts in a way that like alienates Victor Frankenstein's creature in the novel from his own body. For her, it's like something she's taken control of and increasingly, she's able to manipulate her own sort of like modular qualities in order to rescue people towards the end of the text is no longer just a way that she's kind of kept subservient to her creator. So I just think she's an interesting example, because I know it's this movie that I think most of us watch when we're kids. And I realized it's a Frankenstein story after doing our last podcast.

Rosa

So like a more successful creature. Would you say?

Katherine Bergevin

Yeah, I mean, but that's because she lives in Halloween town where everyone is kind of grotesque and falling apart.

Rosa

No. Fair enough.

Katherine Bergevin

But there is this parent -child sort of relationship that it explores too.

Matt Park

I really like when you're talking about her ability to remake herself, because I think that's what the creature never learned or never developed the ability to do, which is he never got over the moment of his creation and abandonment. And he never developed another path or purpose in life beyond, I was created by this guy, Victor, and then he immediately saw me and ran away.

So he was never able to disassemble or reassemble himself. He was never able to make himself into something beyond that kind of origin story and his need for grappling with and eventually obtaining revenge for that. So I think that's great.

For me, I want to talk about kaiju movies. Kaiju, as you may know, literally translates to strange beast in Japanese, although it is more often rendered as giant monster in English. Frankenstein's monster was in a few kaiju movies. They originally wanted Frankenstein's monster to face off with King Kong in the Congo, which I am very glad did not happen, for a number of reasons that I'm not gonna get into, but it sounds like a disaster. After that, they wanted Frankenstein's monster to fight with Godzilla. That also never happened, but they did end up getting Frankenstein's monster into two other kaiju movies where he rumbled with some other baddies, lesser known kaijus. These were not thoughtful films. These were, big monster punches, other big monster films as some of the Godzilla films were.

But those aren't the movies that I'm actually here to talk about. I do wanna talk about the big guy himself. I do wanna talk about Godzilla. And that's not only because my most recurring nightmare that I've had throughout my life has been where Godzilla is chasing me.

Katherine Bergevin

Still?

Matt Park

I grew up watching the Godzilla films and from the time when I was young till fairly recently, I have had nightmares where I am running and Godzilla is just chasing me down. He seems to know where I am and he just follows and I just cannot elude Godzilla. So I have a connection with the guy. It is also the case that there is a Godzilla -ssancee which is overlapping with the Frankenstein-assance. There have been a ton of new Godzilla movies which have also come out lately. And again, I think there might be a connection there in terms of some of the fears that people are having.

And so Godzilla is a tragic figure. And in the good Godzilla movies, in the thoughtful ones that are not just, you know, big lizard punches big monkey, they are about Godzilla being a tragic figure who is created by the hubris of mankind. Ishiro Honda, who was the director of the original Godzilla, once said, "Monsters are tragic beings. They are born too tall, too strong, too heavy. They are not evil by choice. That is their tragedy." And I think the sympathy for Godzilla is of the same tradition as Shelley's sympathy for the creature. Godzilla did not have a choice. He is the product of man's hubris and of atomic weapons tests, which have mutated him and given him the destructive powers of an atomic bomb. Godzilla is angry, disturbed, fearful, suffering as it emerges from the depths. And whether through malice, a desire for revenge, fear, or self -preservation, this is ultimately what leads Godzilla to do what he does, which is come onto land and level cities and lay waste to human life.

This is really, really, I'm gonna be talking about the original 1954 Godzilla film, though I also highly recommending 2016's Shin Godzilla, as well as the 2023 Godzilla Minus One, which just came out. Minus one's pretty awesome. In particular, in the original 1954 Godzilla, there are two scientists worth talking about, and they serve as kind of a touch point for how we're meant to feel about Godzilla. In Mary Shelley, the creature talks and monologues and lets you know exactly what he is thinking and feeling his inner torment. Godzilla, of course, does not talk. He roars. And we don't know exactly what's going on inside the head of Godzilla. But a lot of the better films, they really go out of their way to present Godzilla as sympathetic, as anguished, as suffering.

And in the first film, there are two scientists who kind of serve as our way into the consciousness of Godzilla. The first is Dr. Yamane, who's a paleontologist. And when humankind makes the decision to eliminate Godzilla, he actually grieves. He openly grieves. He asks to be left alone. He's extremely disturbed by the fact that humanity is going to wipe out this creature, which exists not by its own choice, but because people made it so. And he understands that in destroying Godzilla, rather than trying to study and understand Godzilla and extend our empathy to him, we are destroying a one of a kind, a unique species never to be possibly seen again.

The other scientist in the film is kind of the stand -in for Victor Frankenstein or... what the director thinks Victor Frankenstein would have been if he wasn't so terrible. His name is Dr. Serizawa and he literally has a Frankenstein-esque laboratory in his basement. He's got electricity popping and whirring tubes that are running to, you who knows what. It looks exactly like a Hollywood Frankenstein set. And in his secret laboratory, Dr. Serizawa has designed a super weapon called an oxygen destroyer that has the potential of destroying Godzilla. And yet for most of the film, he refuses to use it. He doesn't even acknowledge its existence because he knows that if human beings knew the oxygen destroyer existed, they would want it and human governments would want it. They would mass produce it and eventually it would get out there would be some kind of war and all life on earth would cease to exist because of his invention, because of his creation. So at the end of the film, when he agrees ultimately to use the oxygen destroyer and kill Godzilla, first he burns all of his notes, he destroys his laboratory so that none of that can be used to recreate it. And then he makes sure that he personally stays on the ocean floor with Godzilla and is disintegrated, so that no one can ever get a hold of him and force him to do his experiment again, to create a new oxygen destroyer. And so he stands in as a kind of responsible scientist. He creates something because of the pure desire for discovery, and then having realized this is a terrible thing, he refuses and refuses to use it, and then ultimately when it is used, he tries to make sure that it can never ever be done again.

And so for me, there are a lot of interesting connections there in terms of how Godzilla is influenced by Frankenstein, as well as how the director has updated some of the parts of Frankenstein in terms of making scientists in the film who are responsible and who balance scientific discovery with the good of mankind and their morality and things like that.

The other thing that I think about while watching Godzilla and reading Frankenstein is ultimately Charles Darwin. And I think that both in the film and in the text, Darwin is always lurking. He's always behind us. And I think a lot of the horror comes from some of the realities of the theory of evolution.

In the text in Frankenstein, Mary Shelley is worried that the creature and a bride would eventually replace humanity because they would be the superior species. They would outcompete us. Natural selection would wipe out humanity and replace us with the creature. And similarly in Godzilla, you have this terrible evolution spurred on by nuclear testing in which this enormous creature emerges and then sets about to destroy an entire city. And if he's not stopped, could destroy again, all of humanity. So I think the other thing that Godzilla really makes me think about is really our inability to really and truly deal with Darwin and with the implications of evolution. I think we reach, I think when we think about evolution, we reach a certain point at which we can go no further because the implications are fairly terrifying. And I think there's a fundamental kind of horror to it in terms of life on earth being here by chance. And there not being, anything provable, which makes life more than that. And I think at that point, we reach a certain kind of impasse in which it's frightening. And I think, again, both the text and the film really kind of bring that out for me. So that's my film.

Katherine Bergevin

It is really interesting to think about how, a text like Frankenstein with the way he describes the possibility of humans being like supplanted by this, you know, race of, I think they do use the word race, like descended from the creature and his bride. I lost track of the grammatical structure of my sentence. He's afraid that humans will be supplanted by this monstrous new quote unquote race, you know, loaded term. And we can see how fiction might've actually, been exploring ideas that would have contributed to the scientific discourse that emerges with On the Origins of the Species, which was published a few decades later. And we know that Darwin was also an ocean explorer who went to the far reaches of the world. And there's this idea of naval exploration that is so important to the plot of Frankenstein. And I think also, in terms of thinking about the boundaries of science, the fear that we like what we know the world, you know, isn't flat. But what happens when we reach the parts we haven't reached yet? You know, like the Arctic or, Darwin traveled to the Galapagos. And we know that, like, there were other people in, like, most of these spaces and other creatures. But to the mind that was creating Frankenstein, like as a European, there was this sense that, like, what if we can't take control of these frontiers? You know, what if in Frankenstein, it's like, what if the creature and his offspring overtake them and are able to out-compete us. And we can see how that then reemerges in the science writing, the avowed science writing later on, which I think is really fascinating.

Rosa

And I would also say that, so not only is there the question and the horror of like, what's gonna replace us? Are we really destined to be the like controllers of the world? But also who's gonna get stepped on, I think is really interesting, right? Or who's in the path of the monster, right? I mean, I think that's one of the things that, you know, my wife and I, we saw Godzilla Minus One and I was just like crying for the whole time, especially at the end, right? Because like, who is in the path of danger? Who's being sacrificed? It's all the people who don't have any other choice. Who are on the outskirts of society, right? The only reason why the main character even survived was that he was a kamikaze pilot who refused to kamikaze, right? And similarly, the people who are left to defend Tokyo are not the warships and not the Americans, but it's the disgraced servicemen. And I think in some ways that's also part of the, not that we should take the side of the villagers in Frankenstein, because they're of course, I don't know if we can say racist, but certainly afraid of the new, afraid of difference. But they are also on...

Katherine Bergevin

And they put they put Justine to death very readily as well.

Rosa (01:03:42.639)

They do, yeah, no, they also do. But the people who shoot at the creature are also sort of on the edges of society, right? They're living, you know, away from everyone. They're also exiles. They're also, you know, physically impaired. So I think that's also part of the horror of both Godzilla and of Frankenstein, right? That like, what, not only is what's gonna replace us, but like what's gonna happen to us as well.

Matt Park

Yeah, Godzilla never caught me in any of my dreams. I don't know if he would have stepped on me or not or what exactly would have happened had he finally, you know, caught me, but I'm kind of glad.

Our next category plays on the titles of two famous horror films. One is Get Out by Jordan Peele and the other is a movie that has been redone a ton of times, Invasion of the Body Snatchers we're gonna do Get Out of My Text and Invasion of the Movie Snatchers. So we're gonna have Mary Shelley take over a horror film and think about what that would look like. And then we're gonna take a classic horror trope from Hollywood movies and insert it into Mary Shelley's classic text and see how that happens.

I'll go first. I'm really interested in Mary Shelley directing something that's horror adjacent, but not really a horror movie, which is Rise of the Planet of the Apes. And I'm really interested because Shelley is so interested in this idea of what would happen if the creature was able to reproduce and replace humanity as the dominant species on the planet. So I wonder what Mary Shelley would do in a film in which we are no longer, in fact, the dominant species in the planet and what she would do with our ape overlords.

I think she would probably imbue them with lots of consciousness and inner complexity. And I think we would end up with a pretty cool film in which Mary Shelley would explore, you know, the inner workings of these apes and their feelings about how they came to be, having been experimented on by humanity, and then their complex relationships with the humans who are still left on the planet. I think Shelley would be an awesome director for Rise of the Planet of the Apes.

Rosa

You know, I also, I think I literally wrote that in our, in the document you gave us, right, that I feel like what makes Frankenstein a horror is not only the circumstances, but you know, the implications of what, you know, she's saying. So like, you say Planet of the Apes, I would be really interested to see what she says for like, Contagion or the Day After Tomorrow. You know, I think Contagion by Mary Shelley would be really fascinating.

Right, since so many of -

Katherine Bergevin

Well, it exists and it's called The Last Man, her book about viral apocalypse. Well, I guess not virus. I didn't have term theory, but yeah.

Rosa

Oh, yeah, you're right. Yeah, why the last man? That's not by Shelley, is it? Oh.

Katherine Bergevin

No, no, The Last Man, Mary Shelley, one of Mary Shelley's other novels. It's about a pandemic apocalypse.

Rosa

Oh, I don't think I've ever, I don't think I know that. That's great. I wonder if.

Katherine Bergevin

Sorry to interrupt you, but I was just saying if you want to see it, it's out there.

Rosa

Okay, well, I mean, I'm looking for a new book, but yeah, I wonder if why The Last Man is based on that. But yeah, no, I think that would be really interesting, particularly, you know, since so much of her ideas are about the abuse of technology and our inability kind of to see the world as it is and to rise to our better natures. The whole point of contagion, right, which I don't know if I can watch after, you know, our last contagion.

Katherine Bergevin

I'll say my husband and I watched The Train to Busan like the night before COVID outbreak became official and that was a mistake. So, you know.

Rosa

Oh no. Oh boy. But yeah, you know, the whole problem with Contagion, right, is that it would have been better, but the niece of the main character, escaped and then told everybody, right? Or he abused his power or something like that. You know, so like, I feel like, yeah, I think that would have been a great thing. And I'll definitely go check out The Last Man.

Matt Park

I also knew nothing about this. This is the first I'm hearing and I also am definitely going to check it out because that sounds terrific.

Katherine Bergevin

It's the Black Death returns in the 21st century after republicanism has replaced monarchy as the mainstream method of government. It's a maybe it's a little bit too on the nose for what's actually been going on in our world, but definitely an interesting read if you don't mind something long.

Matt Park

That's great, thank you. Catherine, what are you having Mary Shelley direct?

Katherine Bergevin

I guess I'm taking this in a bit of a different direction. I couldn't decide, so I went with one of my favorite movies, which is The Shining. And what I think is, I know that the connection is a bit oblique, but I just keep thinking about Mary Shelley trapped in this house in the darkness of the Year Without a Summer with all these like weird men who treated women like garbage and you know, she

kind of stuck with Shelley, like her, you know, Percy Shelley after a certain point and he was always cheating on her and causing her to be thrown out of respectable society. And there is this sort of like haunted house claustrophobia that, you know, you don't want to project too much emotionally onto historical figures, but I wonder what her take would be on a film like The Shining, which is about a family trapped in a house with this man who's losing it, who in a way kind of has almost total power over his wife and child, like certainly physically, because he's just like much stronger and more insane and frightening than them both. And you know, they're trapped in the mountains with the snow.

And I'm curious, because you know, like her texts tend to be so male, like the characters are always all male, like what she would do with a text where you know, you need the mother figure to, you know, not die off or be murdered, but come through and be the hero to save her son. I'm curious what she would do with the text that requires her to investigate, I guess, like the maternal connection, as opposed to the paternal one of the like, you know, Victor as the father of the creature, or something like that.

Matt Park

Shelley DeVaul would have had a much better experience filming with Mary Shelley...

Katherine Bergevin

With Mary Shelley, yeah.

Matt Park

than with Stanley Kubrick.

Katherine Bergevin

Well, Kubrick. Well, he was...

Matt Park

Talking about talking about Uma Thurman and male directors who abuse their female stars, I mean Kubrick was famous. I mean, he abused everyone. He abused male actors as well. But in The Shining, he is famous for having abused Shelley DuVall and kind of putting her through hell. And I think you see that in her performance and the way in which she's frayed.

Katherine Bergevin

Yeah. The scene where she's on the stairs and she's gripping the baseball bat in this way that you just think, why are you not gripping it at the end? But it's also partly because the actress was being just like badgered by him and forced to take all these takes. Like this is the story I've heard about the film. So yeah, maybe Mary Shelley would have been a less upsetting person to work with after you had explained what a camera was, and what a TV was, and why it's scary that the TV isn't plugged into the wall. There'd be a lot of catching up.

Rosa

But, oh, okay, hold on. Are we thinking like Mary Shelley in her original time comes and directs this or like Mary Shelley, the like somehow updated time travel or just like updated?

Katherine Bergevin

I was imagining she was kidnapped from the 19th century in a time machine and brought to the set of The Shining and they were like, Stanley is dead, we need you to take over for some reason. We put all our resources into this, we're counting on you. Like, what would she do to save the movie?

Rosa

Okay, I like it. I like it.

Matt Park

The real monster was Kubrick all along. But he is, I do love his films, I do. And he is, well, I'll let that be. All right, part B. A classic horror trope has taken over Mary Shelley's classic text. Jump scare, final girl, demonic possession, evil slowly walking towards you, cursed artifact, one last scare, evil cult, or a character has been dead all along. What trope and why?

Rosa

I mean, technically isn't the whole book the character has been dead along?

Katherine Bergevin

It has to be someone else who you didn't know was dead.

Rosa

But it has to be someone else. Well, I mean, I think going to like what Catherine was talking about, like the tech bro, Victor the tech bro, when I last taught this and I taught that section where he's just like, where Victor is going deeper and deeper and deeper into these like texts that have to have nothing to do with the real world anymore, right? And are discredited, but he thinks he's found the solution to everything. It just reminded me of, you how YouTube has like this evil algorithm that suggests all this like men's rights activists material, right? And so like kids who are watching like Minecraft videos, then click on like a men's rights activist video, and then that brings them to another one, and that brings them to another one, and that brings them to another one.

But I feel like that might be a really good idea, right? Like that Victor is actually part of this like evil cult of men's rights activists or insert thing here that sort of takes over the text.

Matt Park

I went with evil cult as well. I said basically the same thing, that it turns out that everything in Victor's life had been planned by the evil cult. They killed his mother, it wasn't scarlet fever after all. And they drove him, they got him into Ingolstadt and they placed in front of him, you know, Paracelsus and Cornelius Agrippa to make sure he got the right ideas. And then Kempe and Waldman came in and they made sure to continue directing him in the natural sciences so that he would eventually be able to do what he did. Does that make sense? No, not necessarily, but do I really like evil cult and conspiracy movies? Yes. So I'm willing to shoehorn that trope into the text and posit that an evil cult was behind it all along. And at the end of the film or at the end of the text, the evil cult emerges and embraces the creature. They create a wife for him and they move on with the new man to take down all of humanity.

Katherine Bergevin

You should write it.

Matt Park

I should not.

Katherine Bergevin

I did not foresee evil cult playing such a prominent role in either of your responses. I mean, I'm intrigued. I was like, what? Interesting. My answer was final scare. And it was that we go back to the sort of it's the shack in the Orkneys where he had built the the would be bride of the creature. And then he, you know, he destroys her. But imagine if the final shot of the film or final text included in the novel was then that being like opens its eyes and begins to move. What comes next after that? Will it become like a fisherman's wife just out in the Orkney's or will you know the fall of humanity ensue?

Rosa

That's awesome, especially because, you know, the whole, the ending is so unsatisfying, right? Because the creature, maybe he dies, maybe he doesn't.

Katherine Bergevin

I don't believe it. I don't think he killed himself.

Rosa

No. Not at all. So like, he, you know, he comes back and his bride is there. Dun-dun-dun...

Katherine Bergevin

But she's married to a fisherman in the Orkneys. Then it just becomes like a romantic comedy. Where they're competing for the girl.

Rosa

I'm into it. I'm into it.

Matt Park

Now that you should write. That sounds like a better screenplay than Matt's ridiculous evil cult is pulling all the strings screenplay, which has been done.

Katherine Bergevin

I think we can combine them. We can synergize these ideas into the ultimate Frankenstein adaptation that will make us all billionaires once we sell it.

Rosa

Absolutely.

Matt Park

I mean, could we sell it to Netflix? Like, yeah, could we sell it to Netflix? Yes. Would it make money? Sure. Would it be something that we would be proud of? No, but we would make money. So I'm okay with that.

Katherine Bergevin

Speak for yourself. Speak for yourself, man.

Rosa

I would be very proud of this.

Matt Park

Fair enough, maybe I'm being too harsh. You know what? I've seen the light. Let's do it. Let's make the money.

Rosa

You heard it here first.

Matt Park

All right, that leads us to our last category. Quote from Frankenstein, it is true we shall be monsters cut off from all the world, but on that account, we shall be more attached to one another. This is a bleak novel. And this actually came up, we had a Bard Sequence Seminar Conference just this past weekend. And one of the things that came up was just how bleak the novel is and the ending and all the suffering that happens during the novel. And so one of the things I said is I don't know that it is the job of authors to give people hope.

I like a lot of bleak things. I enjoy bleak films and bleak texts. And I don't particularly see it as the job of an author to give me hope. I think that if I want hope from a text, I need to find it. I need to be an active reader and look in there and find it. But, you know, it kind of got me wondering, should we take horror to task for being so bleak sometimes?

Am I wrong? Do authors, do writers, do artists have a job to provide people with hope or to provide them with answers or a better way, something to look forward to, something to grasp onto amidst the maelstrom? Or do we just embrace it? Do we embrace that things can be terribly bleak sometimes and just be okay with it?

Rosa

I mean, I think one of the issues that I have with some horror is that it's not only relentlessly bleak, but gratuitously violent in a way that's not... that doesn't do anything. Like, Get Out is violent and especially very bloody. And I always have qualms about showing that last scene when Chris is leaving the house because it is just like, one death after another after another and he's taking joy in it, but it means something, right? These people have tortured him and he's getting revenge on them and he's getting revenge on them for so many things. And so that has a point. And I think what we can take the horror genre to task for is just this rise of just gore with no point. Why are we watching this? Why are we doing this? What is the saying? And I think, that's the problem that I have with a lot of horrors. That is just like, why? You're not providing a catharsis. You're just sort of, it's tragedy porn, right? We don't need to see it. I don't think authors or artists are necessarily, not everything has to be for everyone and not everything has to have like a message. I think, I think there are some things that need to have a point to it, and violence and horror is one of them.

Katherine Bergevin

Especially with the way that female characters and women's bodies are so disposed of in a lot of horror movies. I think this is declining a little bit in more recent cinema, but there can be a way that it feels like the gratuitous violence is degrading the human condition in a way that sort of bleeds out of the film. Like to, I don't know quite how to put it.

I feel like a valuable piece of art should at least make us think and feel something new that enhances our experience of inhabiting our minds and society. And if you leave something just feeling kind of like the human body has been cheapened in some way, or human life has been cheapened in some way, then I kind of agree with you. I think that is something we should interrogate if we find ourselves drawn to media that, has that effect.

Matt Park

I'm not drawn to the gory stuff. I'm not drawn to graphic stuff. I'm not drawn to buckets of blood and intestines spilling out and things like that. And I don't think that is inherently bleak either.

Katherine Bergevin

No, I agree. Like it can be kind of just cheesy shock value that I can understand why some people find it fun.

Rosa

For example, you know, there was that Frankenstein stage show that the National Theater did with Johnny Lee Miller and Benedict Cumberbatch who played Victor and the creature and they like switched roles, right. And for the National Theater production, there's a scene in the play where the creature, rapes Victor's wife, right? Right, it's a sexual assaults her. And, you know, that's, it's in the play and it takes place at the back of the stage on the bed. And if you're, the way the National Theater Live, you know, usually does it is it just shows the stage, right? It's just sort of like you're watching it. That's the whole point.

But for that particular scene, like the camera panned over and then it's like over the bed watching the creature rape her. And it's like, but why? We know what's happening. We can hear it. We can see it. Why do we have to forefront that? Right? What is the, what is that actually saying to us? And so I think the bleakness of that, the bleakness of the outlook of that is not, isn't useful. I don't think it's actually adding anything to the conversation because dystopia is one of my favorite genres. I can read that every two minutes, right? But what is important about dystopia is not how we got there, but how we get out.

Matt Park

That's helpful. If we ever find ourselves in a dystopia, we'll want to know how to get out. Thank God we're not in one right now.

Rosa

Yay.

Matt Park

Things are great! Things are really, really good, the glass is half full. I'm feeling good. Hope you're all feeling great. Things are great.

Rosa

You know, it's just also such a dumb dystopia, like, that we're stuck in. Like, if we were going to be in a dystopia, can't we just like, can't there be some sort of like game or, you know, TV show or some kind of cool social media?

Katherine Bergevin

Soma. So at least we're all like, let's say social media is the Soma, I guess.

Matt Park

Can we all be in Squid Game? Is that the -

Katherine Bergevin

No, dial it back, dial it back.

Rosa

Not Squid Game. Definitely not. I mean we are in Squid Game, aren't we? Isn't that what capitalism is really?

Matt Park

All right, that's the place we end. We end bashing in capitalism as always. Catherine, Rosa, thank you so much. Thanks for joining the Bard Sequence Podcast. It's been lovely, it's been wonderful. Thank you.

Katherine Bergevin

Thanks, Matt. This is awesome.

Rosa

Thanks for having us back.

Katherine Bergevin

And Rosa, I hope to see you and Bella soon as well.

Rosa

Absolutely, anytime.